Inspired by the NYPL, here's my 2017 Australian Reading Calendar, including some old favourites and some on my to-be-read list. Pick a couple or read the whole list. No promises but my goal will be to write about my reading throughout the year. It's good to begin a new year with a reading project, isn't it?

2017 Australian Reading Calendar

January

See what one of Australia's best-loved authors does with the tales of his own life. This one has been sitting on my to-be-read pile for a few months now. It's bound to include stories of hot Western Australian summers, the surf, the bush - perfect reading for an Australian summer.

February

March

Just about everything I know about the Catholic Church, I learned from the novels of former priest, Morris West. He was also a writer much adored by my mother, so much so that his new releases were the obvious Christmas/birthday gift for her for many years. The Shoes of the Fisherman, a novel about the election of a new Pope, was published in 1963. It may be hard to find but I'm hoping it's as gripping to reread as it was the first time I read it.

April

April

I have to confess that Maxine Beneba Clarke's memoir of growing up black in Sydney was a highlight of my 2016 reading. I recognised my own childhood in it - except for one very important thing. My childhood was entirely white. If you haven't read it yet, please, please do, especially if you're a teacher or parent or human being. It will make you see Australia in a different way and given the year we've had, that's a very important thing.

May

Another confession - I haven't read any of Christina Stead's novels (although Hazel Rowley's biography is wonderful and highly recommended). I'm going to remedy that this year by reading her second novel, published in 1936, I promise this is the last book on the list with the Eiffel Tower on the cover but it does promise a love triangle set against a backdrop of political upheaval.

June

2017 marks the 50th anniversary of the 1967 Referendum which gave Indigenous Australians the right to vote and the 25th anniversary of the Mabo Decision which destroyed the concept of terra nullius. There's a lot for me to learn about both events. To begin, I'm going to read Mabo's story.

2017 marks the 50th anniversary of the 1967 Referendum which gave Indigenous Australians the right to vote and the 25th anniversary of the Mabo Decision which destroyed the concept of terra nullius. There's a lot for me to learn about both events. To begin, I'm going to read Mabo's story.

July

|

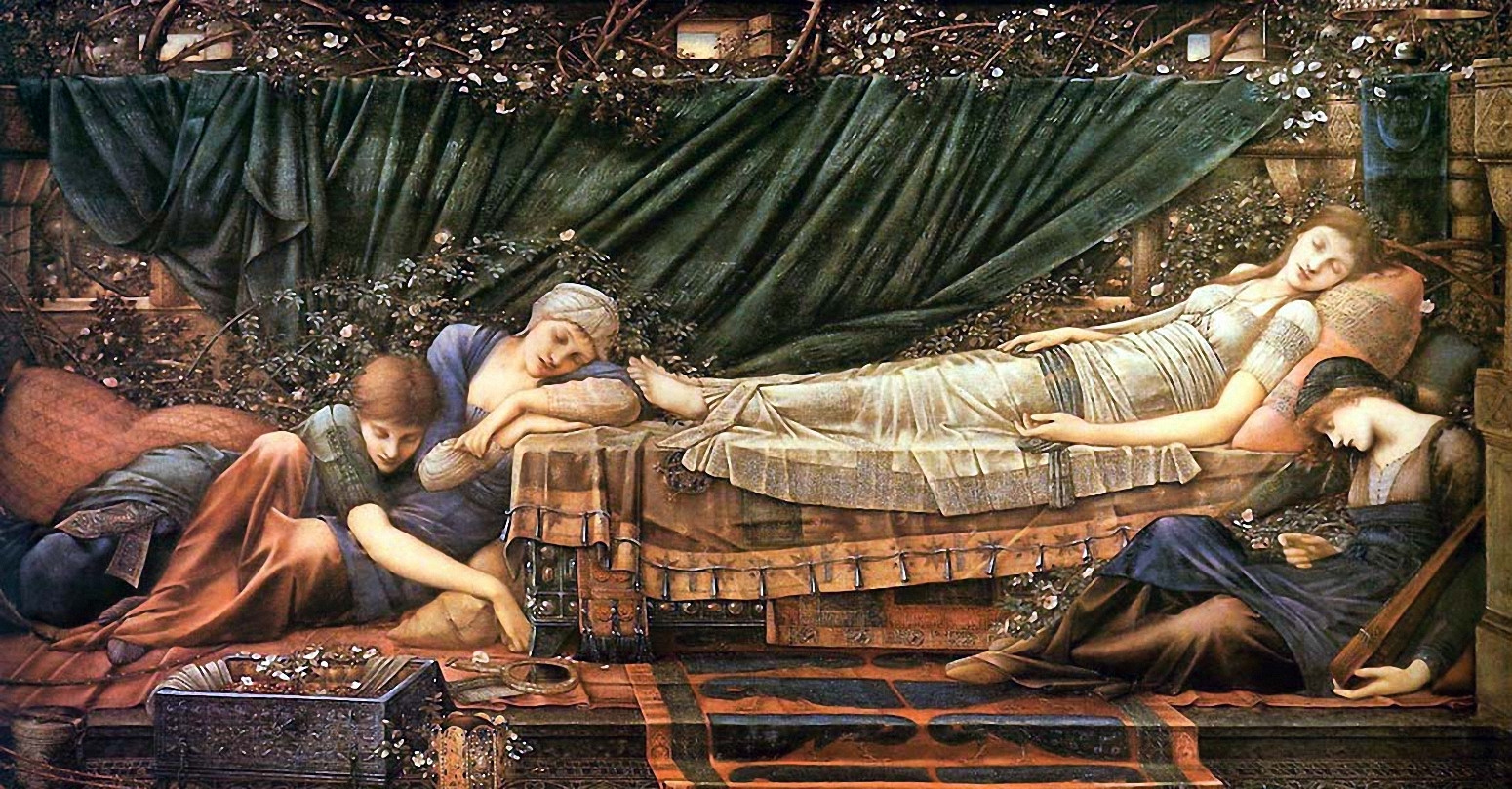

| "The Rose Bower" from the "Legend of Briar Rose" by Sir Edward Burne-Jones, via Wikipedia |

I adore Kate Forsyth's reimaginings of fairy tales and the depths of winter seem to be the perfect time to curl up with her retelling of Sleeping Beauty through the lives of the Pre-Raphaelites. What a combination! If you are curious, she has written about writing Beauty in Thorns on her blog. Begin your pre-reading here.

August

I feel a bit uncomfortable including Georgia Blain's novel on this list. Her death is so very recent and by all accounts the novel's terrain echoes aspects of the author's life. But the novel keeps appearing on 2016's 'best of' list and is probably demanding me to read it. So I'm going to read it before opening The Museum of Words, which the Sydney Morning Herald has gently described as her 'farewell book'.

I feel a bit uncomfortable including Georgia Blain's novel on this list. Her death is so very recent and by all accounts the novel's terrain echoes aspects of the author's life. But the novel keeps appearing on 2016's 'best of' list and is probably demanding me to read it. So I'm going to read it before opening The Museum of Words, which the Sydney Morning Herald has gently described as her 'farewell book'.

September

October

November

Rediscover Joan Lindsay's Australian classic as it celebrates 50 years of publication.That's right, 50 years! I know there's a film and a soon-to-be-released tv series, but let's all go back to the source this year and read the book.

Rediscover Joan Lindsay's Australian classic as it celebrates 50 years of publication.That's right, 50 years! I know there's a film and a soon-to-be-released tv series, but let's all go back to the source this year and read the book.

December

Choosing the final book for the year is tricky. I've gone with a crime novel, Adrian Hyland's Diamond Dove. Another female protagonist, it's a murder mystery set in Central Australia. And Hyland's publisher, Text, promise it's 'the wittiest and most gripping Australian crime novel you'll read this year'.